Tu Er Shen (兔儿神 or simply, 兔神; The Leveret Spirit) is a Chinese Shenist or religious Daoist deity who manages the love and sex between male homosexuals - the patron god of gay men. His name is more often colloquially translated as the "Rabbit God" or "Rabbit Deity".

The religious figure apparently originates from a folk tale in 18th-century Fujian province. In the story, a soldier falls in love with a Qing dynasty provincial official and spies on him to see him naked[1]. The official has the soldier beaten to death but the latter returns from the dead in the form of a young hare, or leveret, in the dream of a village elder. The leveret demands that local men build a temple to him, where they can burn incense in the interest of "affairs of men". The story ends thus:

"According to the customs of Fujian province, it is acceptable for a man and boy to form a bond (qi, 契) and to speak to each other as if to brothers. Hearing the villager relate the dream, the other villagers strove to contribute money to erect the temple. They kept silent about this secret vow, which they quickly and eagerly fulfilled. Others begged to know their reason for building the temple, but they did not find out. They all went there to pray."

Legend[edit | edit source]

The mythology of the Rabbit God was described in Zi Bu Yu (子不語), a collection of supernatural stories written by Qing dynasty scholar and poet Yuan Mei (袁枚, 1716-1798). “Zi Bu Yu” literally means “things of which Confucius did not speak.” It was inspired by the statement that “Confucius spoke of no supernaturalism, feats of powers, disorders and spirits” in the Analects of Confucius. Yuan implied that the anecdote of the Rabbit God should not be taken seriously because Confucius would disapprove of such a tale[2].

According to Yuan, in "The Tale of the Leveret Spirit", Tu Er Shen was originally a man named Hu Tianbao (胡天保) who fell in love with a very handsome, young, imperial inspector in 18th-century Fujian province during the early Qing dynasty[3]. However, because of the inspector's higher status, Hu was afraid to reveal his feelings. One day, Hu was caught peeping at the inspector's bare derrière through a gap in a bathroom wall when the latter went to the toilet, at which point Hu confessed his reluctant affection for the other man. The imperial inspector was outraged and had him sentenced to death by beating for offending a nobleman. One month after Hu's death, he is said to have appeared to an elder from his hometown in a dream, claiming that since his crime was one of love, King Yama, ruler of the Chinese Hades, had decided to redress the injustice by appointing him the Rabbit God. As such, his duty was to govern the affairs of men who desire men. In the dream, he asked the man to erect a shrine to him. When he awoke the elder obliged by exhorting his fellow village folk to raise money to erect a temple to Hu Tianbao and named it the Rabbit God Temple. In return, the Rabbit God responded to his adherents’ prayers without disappointment. Yuan mentioned that people who had underground love affairs, secret agreements and unobtainable desires could visit the Rabbit God Temple.

Yuan finished the story of the Rabbit God with a comment on the popular “bond brotherhood” tradition in Fujian, whereby a man in love with another man would vow to be qixiongdi (契兄弟). Qi means “contract or agreement” and xiongdi means “brothers.”

Yuan Mei’s sympathy for the protagonist, Hu Tianbao provides evidence that during the 18th century, Chinese attitudes toward homosexuality were tolerant to some extent in South China, especially in the area of today’s Fujian province.

Rabbit God Temples became very popular in Fujian province, so much so that in late Qing times, the cult of Hu Tianbao was targeted for extermination by the Qing government.

Research suggests that Hu was an upper-class historical figure who lived in Fujian from the late Ming dynasty to the early Qing dynasty. However, according to Michael Szonyi, associate professor of Chinese history at the department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, the Rabbit God is a pure invention of the poet Yuan, since the image of the Rabbit God does not appear in any other sources from Fujian. While some aspects of the story may be fabrications, the existence of the cult of Hu Tianbao in late 18th-century Fujian is well documented in official Qing records.

The deity can be seen as an alternative to Yue Lao (The Old Man Under the Moon, 月下老人), the matchmaker god for heterosexual relations.

Etymology[edit | edit source]

A derogatory slang word for a homosexual man in late imperial China was tuzi (兔子, rabbit) and rabbits became symbols of homoeroticism. The reason why these animals were associated with homosexual men could be that rabbits in Chinese culture are considered gender-ambiguous. The Mulan Ci (木蘭辭; Ballad of Mulan), a famous 5th/6th century folk song, describes how Hua Mulan disguised herself as a man to enlist in the army in the place of her aged father. Mulan successfully convinced her colleagues that she was a man, and no one suspected her real biological sex. The author of Mulan Ci used the indistinguishable genital characteristics between male and female rabbits as an analogy to emphasise the androgynous appearance of Mulan. The ballad ends with the following verse:

"The he‐hare’s feet go hop and skip,

The she‐hare’s eyes are muddled and fuddled.

Two hares running side by side close to the ground,

How can they tell if I am he or she?"

Anxiety driven by concern about gender ambiguity may be responsible for referring to effeminate men and male prostitutes as rabbits in Chinese folk speech[4]. Perhaps that is also why Hu Tianbao was called the Rabbit Deity/God even though he had nothing to do with rabbits and should not be confused with tuer ye (兔兒爺, the white "Rabbit on the Moon" or Jade Rabbit, the pet of Moon Goddess, Chang'e (嫦娥), sometimes also referred to as the Rabbit God[5],[6],[7]. The Jade Rabbit is likewise associated with homosexuality. According to legend, he was the lunar medicine maker who appeared to the people of a region ravaged by war. He gave them herbal pastries that healed the wounded and the sick, and also came to the aid of a young soldier who, having failed to save his male lover from capture by the invaders, prayed to the moon. The Jade Rabbit responded to his plea by turning an orchid patch into gold. The young man then sold this gold and was able to pay his lover’s ransom[8].

Government suppression[edit | edit source]

In temples, images of Hu Tianbao show him in an embrace with another man. In the folk tale, the sense that the villagers must keep the reason for erecting the temple secret may relate to pressure from the central Chinese government to abandon the practice of worshipping the Rabbit God.

In Michael Szonyi's[9] paper, "The Cult of Hu Tianbao and the 18th-Century Discourse of Homosexuality", which was published in the journal "Late Imperial China" in 1998, he discusses the evidence used by the Qing government in its campaign against religious sects. An official, Zhu Gui (朱珪, 1731-1807), a grain tax circuit intendent of Fujian who, in 1765, strove to standardise the morality of the people with a "Prohibition of Licentious Cults". One of two cults in the provincial capital of Fuzhou which particularly aroused his ire was that of Hu Tianbao. He described the iconology of the cult thus:

"The image is of two men embracing one another; the face of one is somewhat hoary with age, the other tender and pale. [Their temple] is commonly called the small official temple. All those debauched and shameless rascals who on seeing youths or young men desire to have illicit intercourse with them pray for assistance from the plaster idol. Then they make plans to entice and obtain the objects of their desire. This is known as the secret assistance of Hu Tianbao. Afterwards they smear the idol's mouth with pork intestine and sugar in thanks."

Zhu removed the idol, had it smashed to bits and thrown into a river. After this the cult of Hu Tianbao went underground, was forgotten or even ignored. Perhaps it was because of this that a new legend arose saying that the villagers who built Hu’s shrine were sworn to secrecy. They could not tell anyone about Hu or the rationale for the shrine being there, except to those they knew wanted Hu’s specific help[10]. Later official records suggest that the sect was active in the 19th century, but as Szonyi points out, the chief evidence comes from edicts of imperial officials who tried to suppress the practice. Therefore, it is impossible to ascertain how the god was perceived from its adherents' point of view.

Modern interpretations[edit | edit source]

Although Tu Er Shen is popularly revered by some temples, a number of Daoist schools throughout history have considered homosexuality as sexual misconduct.

The story may be an attempt to mythologise a system of male same-sex marriages in Fujian which developed during the Ming dynasty. These were attested to by the scholar-bureaucrat Shen Defu and the writer Li Yu (1611-1680). The older man in the union would play the masculine role as a qixiong (契兄) or "adoptive elder brother", paying a "bride price" to the family of the younger man (apparently, virgins fetched higher prices) who became the qidi (契弟), or "adoptive younger brother". Li Yu described the ceremony, "They do not skip the three cups of tea or the six wedding rituals - it is just like a proper marriage with a formal wedding." The qidi then moved into the household of the qixiong, where he would be completely dependent on him, be treated as a son-in-law by the qixiong's parents, and possibly even help raise children adopted by the qixiong. These marriages could last as long as 20 years before both men were expected to marry women in order to procreate.

Keith Stevens reports seeing images like these in temples in Fujian (Hokkien)-speaking communities in Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and Singapore. Stevens refers to these images as 'brothers' or 'princes' and calls them Taibao (太保), which is probably a perversion of Tianbao. Stevens was usually told that the two figures in an embrace were brothers, and only in one temple in Fujian was he told that they were homosexuals. A photo of an image from a temple in Kaohsiung is provided by Stevens on page 434 of his article, "The wrestling princes", Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society - Volume 42, 2002.

Sadly, the history of Hu Tianbao has been largely forgotten even by the temple keepers. There was, however, a temple in Southern China called “Double Flowers Temple,” where a deceased gay couple was worshipped by the general public. The temple was destroyed by the Japanese army during the World War II and no longer exists[11].

Rabbit Temple in Taiwan[edit | edit source]

In 2005, a Taiwanese Daoist priest or fashi (法師) named Lu Weiming (盧威明) claimed to have made spiritual contact with the Rabbit God. Lu often heard complaints from homosexual Daoist adherents that there was no god to answer their prayers. Believing one of his missions was to tend to the needs of people alienated from mainstream society, he set out to revive the forgotten deity and resolved that should 5 same-sex couples approach his temple for prayers or spiritual help, he would establish a new temple specifically dedicated to the Rabbit God.

Although at that time, even though the temple did not have specific programs for gay couples, 5 couples did indeed turn up. The priest took this as a sign and officially established the Rabbit Temple in 2006. Currently, about 9,000 gay pilgrims visit the temple each year praying to find a suitable partner.

Location[edit | edit source]

The Rabbit God Temple is situated at No. 12, Alley 37, Yonghe Road Section 1, Yonghe City, Taipei (12号,37巷,永和路一段,永和市,台北) [12]. CW Chan of Chinatownology[13] has shot the following photographs to facilitate locating it:

From left to right: 1) The entrance to the alley, no. 37, which leads to the Rabbit God Temple is located opposite this building. 2) The temple is found at the end of this alley, to the right. 3) The unit number sign of the building in which the Rabbit Temple is located.

News report[edit | edit source]

Shortly after its founding, Taiwan's Chung T'ien Television (CTi TV, 中天電視) broadcast a brief report on it during their daily news bulletin (see video:[14]).

Rationale for founding[edit | edit source]

In 2011, Lu uploaded a video to YouTube in which he explained in detail his reasons for setting up the Rabbit God Temple[15]. In short, it was to provide the religious solace sought by the gay community and, via the blessing of the Rabbit God, to give everyone compassion and love.

In a separate upload, he also explained the Daoist view of homosexuality (see video:[16]).

Lu feels that the deity can be seen as an alternative to Yue Xia Lao Ren (月下老人, the matchmaker god for heterosexuals)[17]. He usually advises gay templegoers not to go to Yue Lao, (the nickname of the matchmaker god), since love affairs between men and women are believed to be his responsibility. The deity would be confused by homosexuals' prayers and probably say to himself: "The prayer doesn't seem right. I'll match you with a woman instead."

The Rabbit God is perceived to be an affable deity who is willing to assist his followers in every aspect of life. Since he works for Cheng Huang (城隍), the City God, he has both the erudition and social network in the spiritual world to solve any problem mortals have.

Homosexuals may have an edge in the spiritual world because Hu Tianbao is rather self-abased both because of the way he died and the somewhat belittling title of "rabbit". So if one is willing to believe in him, he will be much more grateful and work harder than other deities.

Television interview[edit | edit source]

In 2011, Taiwan's China News Magazine (華視新聞雜誌) interviewed Lu in a programme entitled, "Seeking peach blossoms in the Year of the Rabbit" (兔年求桃花)[dotbe]:

Rituals[edit | edit source]

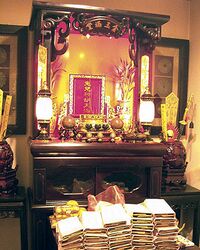

There are several methods of worshipping, asking for and receiving answers from this divine being, but sincerity is what counts most. For this reason, followers should address the god as "Da Ye" (大爺), or "Master", rather than "Rabbit God". Then, those with needs can write down their names, addresses, birthdays and prayers on pieces of paper money and burn them to make sure the messages are sent to heaven.

A devotee seeking a talisman or charm is first obliged to fulfill a requirement - he has to recite his name, address, and date and time of birth to the Rabbit God. Using wooden divination moon blocks (jiaobei; 筊杯 or 珓杯), he must then throw 3 consecutive shèngjiǎo (聖筊, divine answer), namely one block with the flat side and the other with the round side facing upwards signifying a "yes" answer, out of 9 tries before he will be bestowed the blessed charm. It sounds easy but is actually not.

In another form of worship, personal items can be brought before the alter for Da Ye's blessings. It is a Daoist belief that wearing the items will reinforce the power of blessings. Some followers believe that blessed skin-care products are more effective and increase the likelihood of romance. Followers can also take fu (符, paper charms) from the temple, place them under a pillow and pray to the deity to fulfill their wishes before going to bed. The praying is meant to encourage contemplation.

Apart from the spiritual side of the sect, Lu is also concerned about the status of homosexuals in society, and that is a major reason for establishing the temple. "Religions both in the West and the East have long pushed the homosexual community into the margin," he said. "But providence is benign, and love is given to all human beings as equals." He also added that the temple is not merely for gay men, but lesbians as well.

Lu is planning religious gay weddings. He wants to deliver a message that religion recognises the union of homosexual couples and there is no reason why the state should not do the same.

To a 25-year-old internist and adherent who requested to be identified as Philippe since his colleagues did not know he was gay, the temple offered a source of comfort in time of trouble. Admitting that he imagined the shrine would be a bit gruesome before the visit, Philippe noted that the whole experience was similar to that of visiting any other temple.

Although he had a secular upbringing, he still felt the need to seek out comfort in religious faith, to know there is hope he could hold on to, a true love that is not far off. He said he would return to the shrine and give thanks to Da Ye if the dinner date after the gay pride parade the previous Saturday developed into a long-yearned-for relationship.

Analysis[edit | edit source]

"Religions both in the West and the East have long pushed the homosexual community into the margin. But providence is benign, and love is given to all human beings as equals."

Lu Weiming (盧威明), Daoist priest.

New deities and even new religions often emerge to address needs or during times of social change. The founding of the Rabbit God Temple in Taipei is one such example. Since its opening, the temple has attracted not only same sex-couples from Taiwan and other parts of the world but also singles in search of their future partner. On the side wall of the temple is a notice board for visitors to leave a message for the Rabbit God. It may be a request for help in their search for love or a thank-you note.

The emergence of the Rabbit God Temple may be contextualised vis-a-vis 2 related trends in Taiwan:

- Regarding social attitudes towards homosexual issues, Taiwan is one of the most progressive societies in Asia and in the Chinese world. In fact, the 2003 Taiwan Pride was the first gay pride parade in any Chinese-majority society. In Taiwan Pride 2005, the then Taipei's Mayor Ma Ying-Jeou, 馬英九, participated in the opening ceremony and even declared that "being gay is a natural state that cannot be repressed". The majority of Taiwanese residents are of Chinese descent. Their ancestors migrated from Fujian, China to Taiwan during the late Ming dynasty and they may have brought a more tolerant view of homosexuality with them. In addition, homosexuals were not treated as criminals during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan (1895-1945).

- Secondly, Taiwan has the culture of Yue Lao worship. Yue Lao, 月老, or "Old man under the moon" is a Chinese deity who oversees heterosexual love affairs. In many Taiwanese temples, there is a chamber dedicated to his worship. Straight couples or singles in search of love leave messages there. The Rabbit God is thus the counterpart of Yue Lao and is in charge of homosexual relationships.

Gay studies had been neglected until Taiwanese society became more democratic during the late 1980s. The resurrection of Rabbit God worship not only signifies freedom of religion but also shows the public’s increasing tolerance of same-sex love. Looking at world religion in totality, a deity in charge of gay relationships is refreshing news. In many countries, religious condemnation and criminal persecution of homosexuals is par for the course. In a landscape of bigotry and ignorance, the Rabbit God arises as one who not only does not denigrate gay individuals but assists them in their search for love. That explains the international interest in the Rabbit God Temple.

Rabbit God in popular culture[edit | edit source]

The Rabbit God's Matchmaking (TV serial)[edit | edit source]

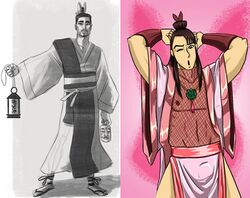

Tu Er Shen was the main character of a hit 2010 Taiwanese television drama serial entitled, "The Rabbit God's Matchmaking"兔儿神弄姻缘.

Tu Er Shen Origins (comic strip)[edit | edit source]

In 2018, a freelance artist based in Boston, Massachusetts named Cam Lee who enjoys drawing comics and fan art uploaded a page of comics depicting the origin of the Rabbit God to commemorate National Coming Out Day[18].

Kiss of the Rabbit God (short film)[edit | edit source]

- Main article: Kiss of the Rabbit God (short film)

[dotbe/bmCw-e72zs8]

In 2018, Chinese-American filmmaker Andrew Huang was asked by London-based culture platform NOWNESS to create a film on the theme "define sex." As a queer Asian, Huang had yet to be tasked with the challenge of representing his sexual identity on screen. This challenge was a loaded one. Having grown up with a deficit of queer Asian visibility onscreen along with the frequent stigmatisation and devaluing of Asian male bodies in Western visual culture, being asked to create a piece centered around queer Asian characters became a dauntingly personal journey for him to unpack these issues, while also crafting a story that he felt enriched their collective imagination of what queer Asian male love, sex and intimacy could aspire to be.

On a trip to Mexico City, Huang encountered an exhibition on Xōchipilli, the Aztec god of flowers and patron of gay love. The story of Xōchipilli inspired him to redirect his lens towards his own Chinese heritage, through which he found the Qing dynasty story of the Rabbit God. This research led him to craft a narrative in 2019 about a Chinese restaurant worker who encounters Tu Er Shen as a ghostly visitor. Nightly visits from the god blossom into a tryst that empowers the boy to release his sense of trapped invisibility and embark on a journey of sexual awakening and discovery. Interweaving his personal family history in the Chinese restaurant business with the richness of Chinese mythology, Kiss of the Rabbit God is a confession and a love letter to his queer Asian community and tells the story of a lover's quest for self-possession to own one's desire and unlock sexual intimacy through spiritual embodiment.

Other Rabbit God documentaries[edit | edit source]

2015[edit | edit source]

2016[edit | edit source]

[dotbe/kFD2DkaFjSI]

2017[edit | edit source]

[dotbe/Y7odncJCoKE]

Zhang Zhongqiang, a fifth generation clay sculpting craftsman, shares the history of the folk craft of sculpting Rabbit God figurines and also demonstrates the production processes.

2018[edit | edit source]

[dotbe/wOS4ONtkjaY]

The Rabbit God is a symbol of old Beijing. Figurines depicting the deity are usually sold during the Mid-autumn Festival in Beijing. The figurines are said to bring good luck, good health, and safety. This documentary invites a fifth generation clay Rabbit God sculptor to tell viewers more about the history and story of the Rabbit God.

2019[edit | edit source]

[dotbe/Si9EdjXveEs]

Facebook group[edit | edit source]

On 10 August 2020, a public Facebook group named Tu Shen - Journey to the West was set up by Edward H. Sebesta for those who visited New Taipei City to see the Rabbit God Temple to share their experiences and thoughts[19].

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- Michael Gold, "Taiwan's Wei-Ming 'Rabbit' Temple Draws Gay Community", Reuters, 19 January 2015[20],[21].

- Michael Gold, "Taiwan's gays pray for soul mates at 'Rabbit' temple", Reuters, 19 January 2015[22].

- Amrutha Gayathri, "Taiwan Monastery Holds Country’s First Same-Sex Buddhist Wedding", International Business Times, 13 August 2012[23].

- CW Chan, article in Chinatownlogy, "Gay Rabbit God Temple 兔儿庙", 2011[24].

- "Rabbit God Temple", Qualia Folk, 8 December 2011[25].

- The Ultra Supreme Elder Lord's Scripture of Precepts(太上老君戒經), in "The Orthodox Tao Store"(正統道藏).

- Kang, Wenqing, 2009, "Obsession: Male Same-Sex Relations in China, 1900–1950", Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp 19, 37-38.

- Ho Yi, Taipei Times article, "Taoist homosexuals turn to the Rabbit God", 21 October 2007[26].

- Keith Stevens, "The wrestling princes", Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society - Volume 42, 2002, pp.431-434

- Michael Szonyi, "The Cult of Hu Tianbao and the Eighteenth-Century Discourse of Homosexuality." Late Imperial China - Volume 19, Number 1, June 1998, pp. 1-25, The Johns Hopkins University Press[27].

- The Great Dictionary of Taoism"(道教大辭典), by Chinese Taoism Association, published in China in 1994, ISBN 7-5080-0112-5/B.054

- Yuan Mei (袁枚), Zi Bu Yu (子不語), 18th century.

- The Ultra Supreme Elder Lord's Scripture of Precepts(太上老君戒經), in "The Orthodox Tao Store"(正統道藏).

- "A guide to gay Taipei", GayTaipei4u.com:[28].

- Allister Chang, "Exploring Gay Taiwan", Passport Magazine:[29].

- Hernestus, "RABBIT GOD TU ER SHEN IS THE CHINESE DEITY OF GAYNESS", Antinous the gay god, Blogspot, 27 September 2019[30].

- Xueting Ni, "Tu Er Shen: Patron of Homosexual Love", Snow Pavilion, 26 May 2019[31].

- https://www.gagaoolala.com/en/videos/1390/kiss-of-the-rabbit-god-2019

External links[edit | edit source]

- YouTube video, "Rabbit Temple in Taiwan for gay men"[32].

- YouTube video, "Gays worship at Taipei's Rabbit God Temple seeking life partners"[dotbe].

- Daoist Master Lu Weiming's YouTube channel:[33]

- Tu Shen - Journey to the West, Facebook group:[34].

Acknowledgements[edit | edit source]

This article was written by Roy Tan.